Predict the impact of a research paper before it is published.

Study in BERT, statistics, and radioligand therapy

Find a full story behind this project in this medium post.

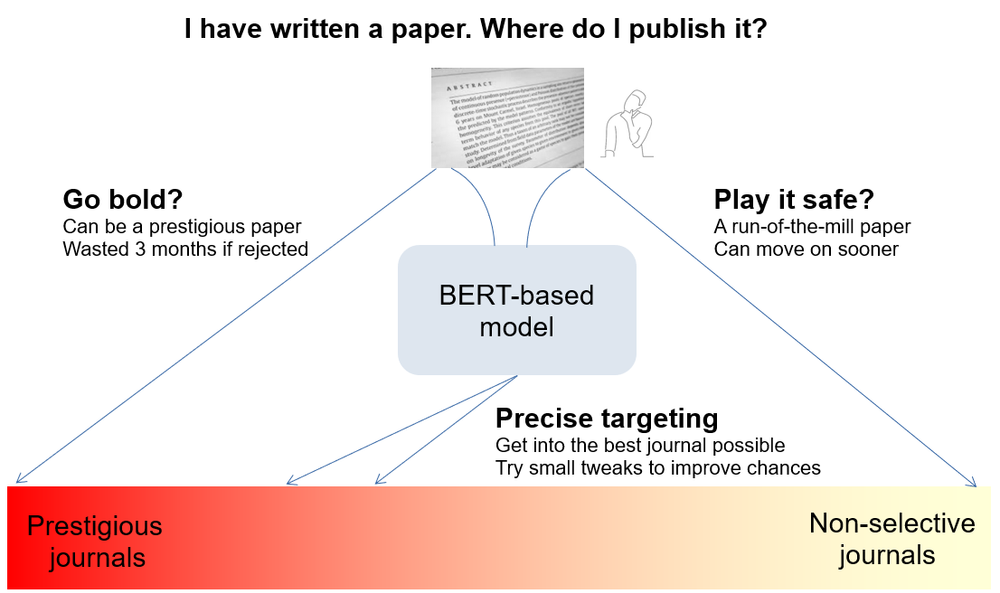

At the end of a research project, scientists face a critical choice: where to publish. Careers are built on landing papers in top-tier journals, but those slots are fiercely competitive — sending every manuscript to Science is a fast track to frustration. Playing it safe with a local conference proceeding guarantees a publication but does little for future funding. If researchers could predict which journal matches their paper’s, they could make more strategic moves.

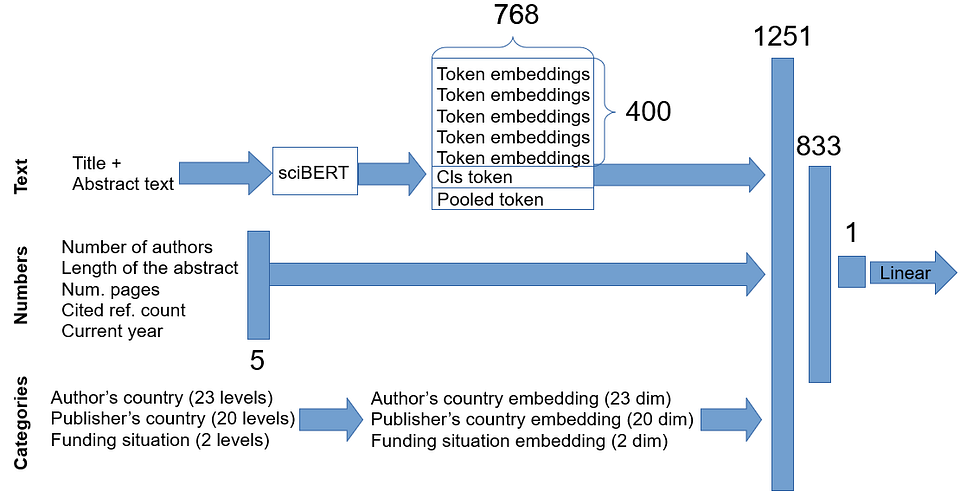

We built a sciBERT-based model that predicts a paper’s impact factor using only the information available at submission — title, abstract, and metadata. The diagram below shows the setup, with numbers marking vector dimensions. In short: we grab the CLS token from BERT, tack on trained embeddings for categorical variables plus scalar metadata, and feed the combined vector through a fully connected layer. The final output is a straightforward linear regression

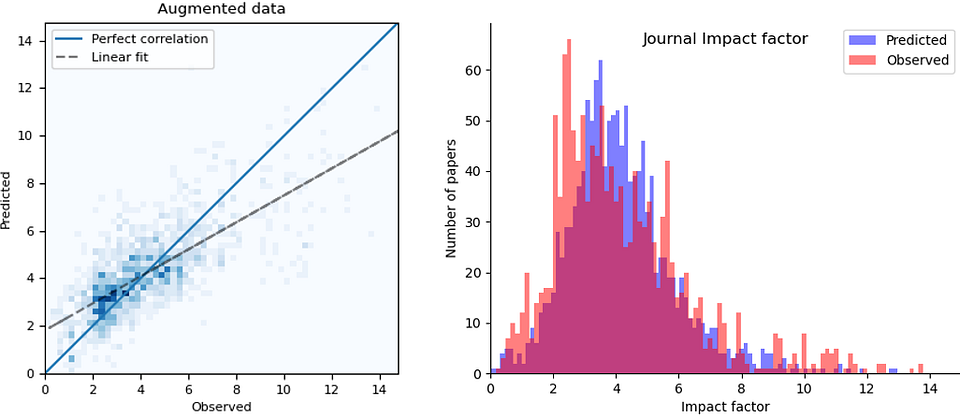

Trained on 4,500 papers from the field of radionuclide therapy, the model delivered strong results, hitting a correlation of r = 0.73 between predicted and actual impact factors. Below, you’ll find a 2D histogram showing the modeled vs. observed impacts, along with 1D histograms for the predicted and actual impact factors in the validation set.

Data augmentation was the key to training the model with our limited dataset. We produced new abstracts mixing in sentences from other abstracts with a similar impact factor. This way we managed to expand the dataset by a factor of 10.

When we compare the distributions of predicted and observed JIFs, one thing stands out: the predicted values are much closer to a normal distribution. Our model didn’t capture two sharp spikes at observed JIFs at 1 and 2.5. As a result, the correlation between predicted and actual values isn’t perfect. A quick look at the mispredicted papers offers a clue: some lower-ranked journals allow unusually long abstracts, turning them into mini-papers packed with experimental details, methods, and even discussion sections. Most high-impact journals cap abstracts at around 250 words, allowing only a broad summary. Our model likely interpreted these overly detailed abstracts as signs of higher

With over 70% correlation between predicted and observed values, this model gives researchers a solid estimate of where their paper might land. Small tweaks to the title and abstract could even push a paper into a more prestigious journal. While having a more diverse dataset could have helped, we would not expect massive gains in predictive power — journal acceptance ultimately comes down to a reviewer’s judgment call, and judgment calls are tough to predict. Looking ahead, we’re interested in pushing this approach further: predicting not just journal impact, but the actual citation index of individual papers. Unlike journal impact factors, citation counts measure the true value of a single project — a metric that could really help researchers aiming to make a lasting mark.