Clinical doses of [F-18]-Fallypride made using microfluidic technology.

Key words: radiochemistry, PET, microfluidic, specific activity, Falypride, F-18, process development

Full story published in Lab-on-a-Chip

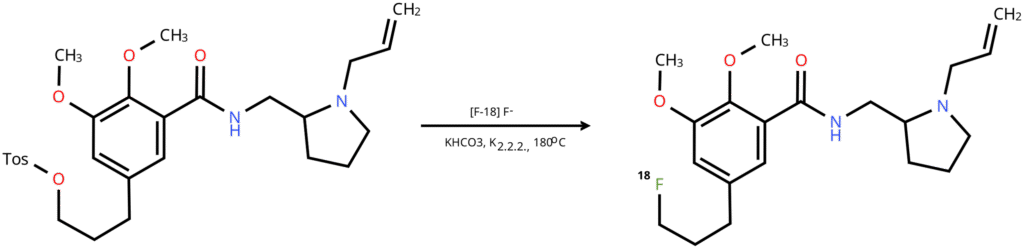

We were the first in the world to use microfluidic technology to produce radioactive drugs for injection into human subjects. Microfluidic technology theoretically offers several advantages for the radiolabeling process, including reduced precursor usage, faster reactions, higher fluoride concentrations, and easier purification. Over time, many major companies in our field have attempted to bring this technology to market, but none have succeeded. Two key challenges have always stood in the way: material selection and the integration of micro and macro components. The materials suitable for manufacturing microfluidic chips can’t withstand the aggressive chemicals used in radiofluorination, and reducing the fluoride volume from milliliters to microliters often results in a loss of valuable radioactivity. Previous solutions have fallen short, either due to rapid material degradation or overly complex designs. As a result, clinicians have been hesitant to trust this technology for producing human doses, given the high stakes involved in clinical production.

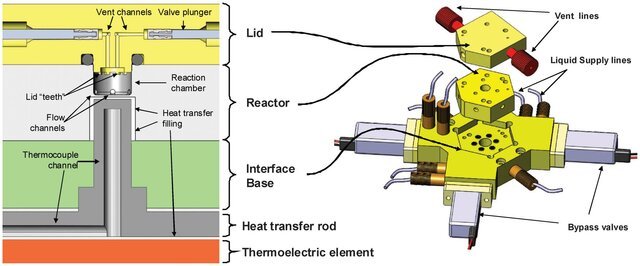

The system that we developed at Siemens was practical and reliable enough to be used in the production of clinical doses of F-18 Fallypride. We used a PEEK and ULTEM for the wetted surfaces of the reactor, eliminating material compatibility issues. That required developing in-house precision machining expertise, but ultimately was the only way forward. Additionally, we designed a miniaturized ion-exchange column that achieved >95% efficiency in F-18 fluoride concentration, successfully bridging the macro- and microfluidic components of the system.

My primary contribution to the project was developing a production and quality control protocol tailored to the equipment, production environment, and the specific needs of the clinical trial. The project posed a series of interconnected challenges. On the equipment side, the extremely high concentration of the radioactive solution required precise liquid transfers. With a total volume of concentrated radioactivity as small as 15 μL, losing even 1 μL could result in a 10% loss in production efficiency. On the chemistry side, radiofluorination had to be performed under a poorly understood temperature profile, since it was difficult to measure the temperature inside a 45 μL PEEK reactor, which does not conduct heat. This lack of temperature control made the impurity profile unpredictable, placing strict demands on the purification process. At the same time, production personnel wanted to avoid toxic solvents in the purification step to eliminate the need for a reformulation process in the workflow. From an imaging perspective, the specific activity had to be as high as possible because the clinical trial aimed to visualize dopamine receptors in the brain, and a low specific activity product would not be effective for targeting this low-abundance receptor. The challenge, then, was to produce a pure product with high specific activity while avoiding post-HPLC reformulation, all while ensuring the process could tolerate some errors from production technicians.

The challenge of liquid transfer fidelity was resolved using precise syringe pumps to generate pressure. I developed a robust sequence of gas pushes capable of moving 45 μL of liquid through 15 feet of plastic tubing while ensuring that at least 44 μL reached the other end.

On the chemistry front, instead of controlling temperature and impurity profiles, I focused on enhancing the purification system’s capacity to handle even the worst-case scenarios. Using a 4.6×250 mm column to purify just 1 mg of material eliminated contaminant peaks near the target compound. Even in cases where impurity levels were unusually high, the semi-preparative HPLC column effectively managed them.

Additionally, I optimized the pH of both the reactor effluent and the HPLC eluent, wich allowed me to replace traditional acetonitrile with ethanol. This switch made the HPLC eluent non-toxic, allowing the production technician to simply dilute the fraction to the required ethanol concentration instead of reformulating it.

Another key improvement involved addressing factors that lowered specific activity. I discovered that Teflon tubing and Kalrez O-rings in the path of the highly concentrated F-18 fluoride solution were major contributors to reduced molar activity. With 75 GBq of a high-energy beta-plus emitter concentrated over just a few mm² of Teflon, the polymer degraded quickly, releasing unwanted F-19 fluoride into the solution. Updating the preventative maintenance protocol to replace these components weekly allowed me to use non-fluorinated plastics and achieve a specific activity of up to 750 GBq/μmol—nearly five times higher than previously reported.

Once the process was developed and successfully tested in-house, I transferred it to the radiopharmacy at UCSD for validation at a level sufficient for an IND amendment. The transfer involved installing equipment, developing SOPs, training production personnel, and integrating the process into the site’s workflow. After several practice runs, live patients were treated with the material produced by our synthesizer, making it the first to accomplish what hundreds of publications from dozens of research groups had worked toward for over a decade