Full story published in PLOS One.

Key words: electrolysis, radiochemistry, inflammation, PET, COX-2

Where does it hurt? This is often the first thing a doctor asks when you come into their office. Most of the time, the underlying cause of pain is inflammation. Most painkillers on the market, from Tylenol to ketorolac to ibuprofen – they are anti inflammatory agents, inhibiting cyclooxenazes, the enzymes that start the inflammatory signaling cascade. One subtype of cyclooxegases, COX-2, is specifically associated with induced inflammation, often caused by cancer. Its close sibling, COX-1, has a broader biological role and is often found in normal tissue.

So, since there are so many COX-2 inhibitors on the market, radio labeling of a COX-2 inhibitor seems like a reasonable approach to image inflammation. Indeed there have been a few attempts, but they were plagued by two issues. Often the probe was metabolically unstable, and the fluoride accumulated in bones more than in the target tissue. Alternatievely, radiolabeling killed the binding affinity and the there was no accumulation in the target tissues.

That’s why I was so excited when reading the original paper on the chemistry of celecoxib I saw a compound shown on the picture above. It has a fluorine atom, and not just any fluorine atom, it is a fluorine atom, attached to an electron-rich aromatic ring, a spot known for its metabolic robustness.

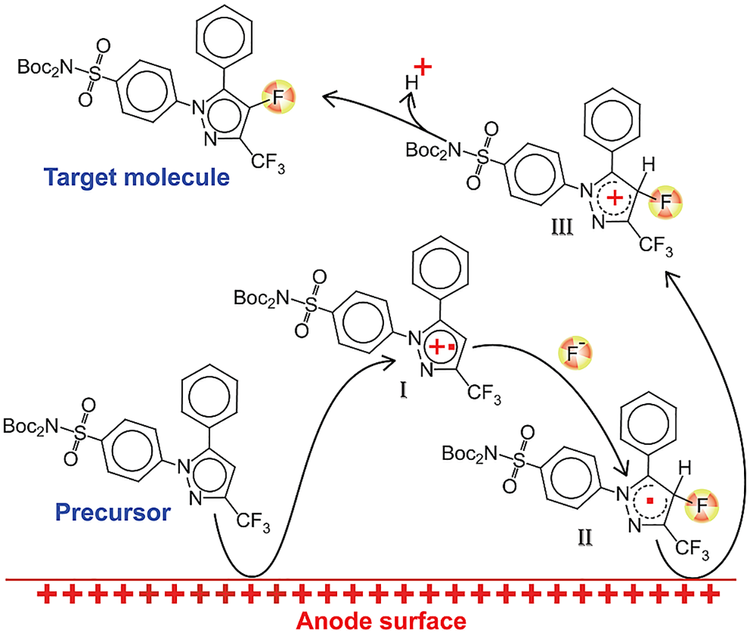

Trouble is, that attaching F-18 to an aromatic ring is problematic in most cases, and when we deal with an electron-rich heteroaromatic ring, it is nearly impossible. To solve this issue we draw inspiration from an arcane part of organic chemistry – preparative electrochemistry. There is a substantial body of literature on the selective fluorination of all sorts of molecules, but radiochemical version of this reaction was virtually unexplored before us. The reaction has three key steps: first, the substrate is oxidized on the electrode and a cation radical is formed. Second, this positively charged particle reacts with the fluoride source and the resulting neutral radical is oxidized again to make a cation, which loses a proton to produce the final product. Notice that oxidizing an aromatic ring, even an electron rich one like pyrazole, takes quite a bit of potential. We did our experiments at above 2.5 volts, so all other reactive groups had to be protected.

The key parameters of the electrolysis are the voltage profile, electrode material, solvent, electrolyte and the chemical form of the fluoride. The original papers on the cold electrolysis used neat teraethylammonium fluorides as both electrolyte and the source of fluoride at the same time. We wanted to move away from having an excess of cold fluoride, and managed to replace the bulk of it with an inert electrolite, like tetrabutyl ammonim perchlorate. Unfortunately, but as a fluoride source, alkylammonium fluoride was irreplaceable Once I lowered total fluoride concentration below certain threshold, the reaction just stopped. So, I had to settle on carrier-added reaction, a big problem, as it turned out later. Additionally, we optimized the time-profile of the potential of the electrodes, temperature of the reaction, electrode material and shape. We settled on Pt clumps for the electrode and -0.5 to 2.7V pulsed potential for electrolysis at room temperature.

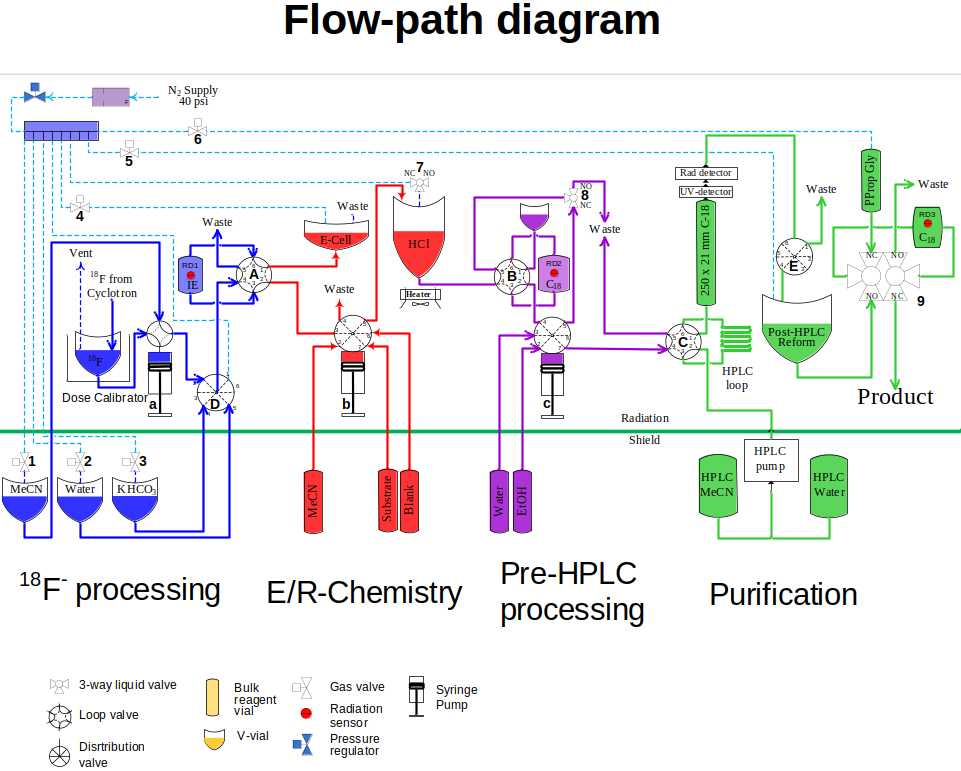

To support the electrochemical reaction, subsequent deprotection and downstream purification, I built a remote-controlled synthesizer that was operated from a touchscreen outside of the hotcell shield. The full flow diagram of the machine is on the picture to the left. Briefly, it had a subsystem for fluoride preparation and drying. From there, fluoride was released in the electrochemistry subsystem that also contained a second reactor for deprotection. After the chemical transformations were complete, the reaction mixture was moved to a pre-purification module to remove the bulk of reagents, and then to an HPLC-purification and reformulation unit. In the end, the system was capable of producing up to 10 mCi of the target product from a cyclotron run, formulated ready for animal injections.

The system demonstrated reliability remarkable for an experimental setup. Several dozen of runs were done to produce doses needed for pre-clinical evaluation of the target molecule.That was in part due to the feedback that was collected from syringe pumps, radiation, pressure and flow sensors installed at critical locations throughout the system. Malfunctions were identified early and the operator could intervene to salvage a run that would otherwise be ruined by an incomplete transfer or a small gas leak.

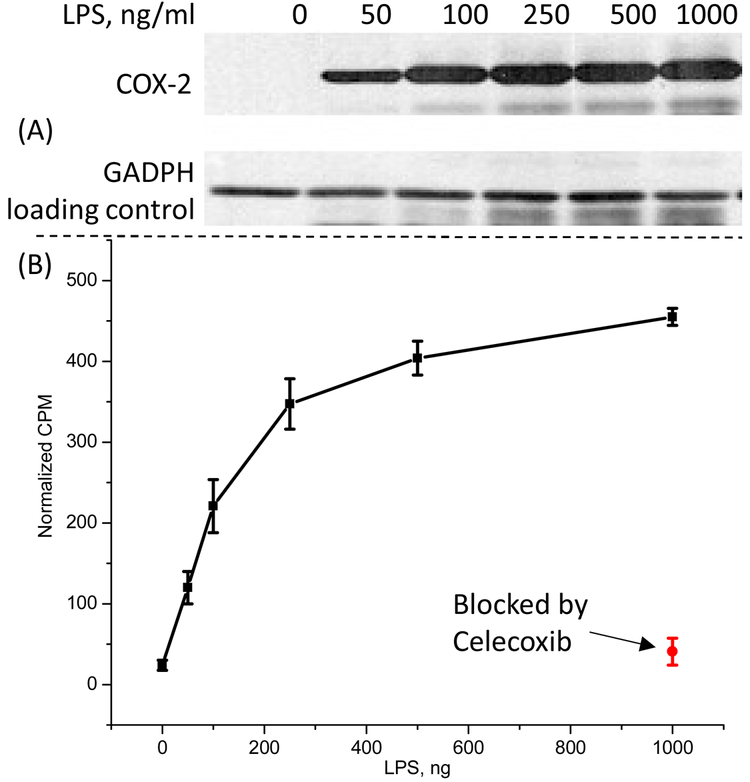

In vitro validation was done using microfage-like cells activated with various levels of endotoxin. The idea is that macrophages will increase COX-2 expression in the presence of the endotoxin, very much like it happens in the inflammation process. After optimization of the protocol, we demonstrated that the target molecule accumulation increased concurrently with the increase of the COX-2 expression and was completely blockable with cold celecoxib – a strong support for the specificity of the molecule.

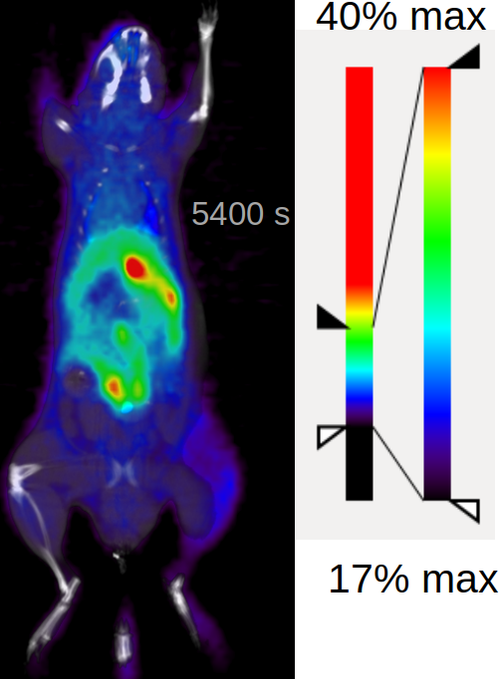

Metabolism studies with healthy mice found almost no metabolic degradation of the target molecule after 1 hour in vivo. Organic extracts from all major organs showed only parent material; aqueous extracts did contain metabolite, but the total activity in aqueous fractions did not exceed 5% of the injected dose. The primary excretion mode was through the gallbladder, making the small intestine appear to be the site of high accumulation due to the radioactivity in the feces.

Dynamic PET of healthy animals (image to the left) confirmed that there is no trace of the bone uptake and the molecules clears away after 30 min, this is really good for the potential imaging tracer. Going forward with the further in vivo validation made no sense given the specific activity we could achieve with carrier-added method.

In summary, we developed a tool to make molecules that are not attainable otherwise. Radiolabled COX-2 inhibitor presented here overcomes the stability challenge of PET imaging of COX-2 while retaining affinity to the target, which makes it a good candidate for future development into a COX-2 imaging agent. Improvement in specific activity is critical for further clinical translation.